Back to School with the Craft of Writing: Lessons from Charles Baxter, Walter Mosley, Elizabeth George, Ben Percy, and Richard Russo

I can write. I can write a statement like “Where’s the coffee?” and realize that it is not a statement but a question fraught with suspense. Then I can write “We’ve run out” and realize that a crisis will ensue.

Conjuring up a fat novel out of thin air, however, is not a basic Reading-Riting-Rithmatic skill learned in third grade despite one’s inattention. After taking the baby steps of “my summer vacation was fun,” fashioning a novel is like climbing Mt. Everest. All right, I confess, the mountain metaphor comes from Charles Baxter. I attended a writer’s conference (it enhances sanity to occasionally leave the house), and Baxter said, not to me specifically (I was a butt-on-the-seat), that it didn’t get easier: writing each novel was like facing another mountain to climb. If an accomplished award-winning profound author like Baxter finds each book a struggle against gravity and fear, what are flatlanders like me to do?

Reading the wisdom of others is a reliable tactic. The number of books on writing is vast and not all are tailored to your needs. Here are a few I admire.

I would not have started a novel if I had not read on a plane Walter Mosley’s This Year You Write Your Novel. Mosley, creator of African-American investigator Easy Rawlins, provides the essential lesson—get started. I learned that I did not have to begin that middle-school terror, an outline. Roman Numerals, Capitals, lowercase letters, indents within indents to be graded—need I say more. If I had a concept, I could wing a draft. You may recognize this as the “seat-of-the-pants” approach. The term I prefer is “builder” with an ad-hoc blueprint. I concoct a rough synopsis, and after drafting out about seventy pages, I outline. I go back and forth from quasi-free writing to structuring. (In defense of organization, there are many examples, including prolific C.J. Box who writes his novels on top of a detailed outline.) Mosley offers more advice, but his book is less dissertation and more helpful shove.

For something closer to a dissertation complete with subtitle, there’s Elizabeth George’s Write Away: One Novelist’s Approach to Fiction and the Writing Life. George is an American writer who outdoes the Brits on their home ground of literary mysteries with her Inspector Lynley mystery series. In Write Away, she provides a breakdown with illustrations from other writers (Toni Morrison to Stephen King) on character, plot, dialogue, scene, etc. George offers thorough advice on how to generate and how to control the tens of thousands of words that become a book.

Since I mentioned fear-master Stephen King, he has On Writing: A Memoir of The Craft. The “memoir” part intrigued me most. Like King, I’m from Maine and recognized the places and types he describes. While King grew up in down-and-out mill-town Maine, I grew up in farming Maine with Robert Frost scenery, and that has made all the difference.

To continue down the dark path of horror, Ben Percy’s Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction discusses renditions of violence, suspense, and the supernatural. His workshop-style essays draw examples from canonized novels, comics, popular movies, and The Game of Thrones. Percy, whose characters in Red Moon are contemporary werewolves, takes on the tension between “serious” literature and “fun” genre to rise above it, or descend below, in exploring how to be “a writer and a storyteller.” Percy’s Thrill Me is published by the independent nonprofit press Graywolf (of course a wolf), which also publishes “the art of” series on writing, including Charles Baxter’s The Art of Subtext.

Other books probe writers’ sensibilities, the strange choices they make in art and life, and in Richard Russo’s words, the challenge of “getting good” and staying good. I’ll always read Russo, and his essays in The Destiny Thief are accomplished and self-deprecating enough (an old girlfriend says to him, “I never dreamed you had books in you) to carry off big proclamations: “The best humor has always resided in the chamber next to the one occupied by suffering”; “Hunger has no business preceding ability, but it always does, with no exceptions.” Russo’s version of Charles Baxter’s mountain is in this question: “could it be that the writer has to reinvent himself for the purpose of telling each new story?”

In honor of Toni Morrison, I’m about to read essays of hers in The Source of Self-Regard which interweave the role of writing with life-and-death social issues. If I want comfort, I return to Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings. While Welty is capable of savage wit in stories like “Why I Live at the P.O” and “Petrified Man,” her memoir is gently observant. Welty offers reassurance that you can be a writer even if you are not a Hemingway-esque brawler and bruiser. You can be a writer even if your parents love you.

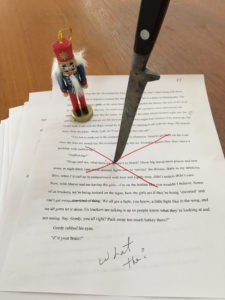

Murder Your Darlings