April, Domestic Violence Books, a Survivors Memorial, Hope and Beauty Reborn

Hidden Hope

It’s spring. Rebirth abounds in the cold north, songbirds celebrate their return, and flowers dare display their pastel heads. It is not all bouquets since tragedy persists in a pandemic not fully conquered, international strife, and the killings of people of color. Homo sapiens cannot seem to learn live-saving lessons. At the best we are dunderheads who don’t get it, at the worst shuttered minds caught in cycles of violence.

Now I’m going to skip that thing about saying April is the cruelest month because it’s February, armpit of the year. April, according to the promoters-that-be, is a special month for at least thirty sublime-and-ridiculous causes. A partial list includes, and I’m reporting not judging, Math Awareness Month, Black Women’s History Month, National Arab American Month, National Car Care Month, Confederate History Month, National Soft Pretzel Month, National Child Abuse Awareness Month, and Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month–SAAPM..

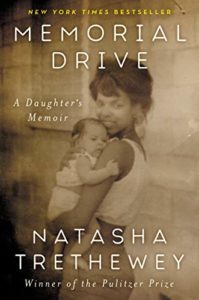

Child abuse and sexual assault run through books I’ve read winter to spring, randomly chosen. For nonfiction: Natasha Trethewey, Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir; Delia Ephron, Sister Mother Husband Dog; Becky Cooper, We Keep the Dead Close: A Murder at Harvard and a Half Century of Silence. For fiction: Delia Owens, Where the Crawdads Sing; Sadeqa Johnson The Yellow Wife; Sejal Badani, The Storyteller’s Secret; Kristen Lepionka, The Last Place You Look, and Jess Lourey, Unspeakable Things. Two caveats. First, not all is grim—they are journeys toward justice, hope, and life recovered, and many entertain thrills, fun, and romance. Delia Ephron’s essays contain pleasant fluff; however, one concerns how her mother’s unrelenting standards and disappearance into alcoholism warped Delia’s childhood. Second, men also write about abuse, and a few that pop to mind are Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Richard Russo, and James McBride.

The starkest of the books above is Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, by Pulitzer Prize winner and former U.S. Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey. Though familiar with Trethewey’s poetry, I did not know of the trauma that haunted her: when she was nineteen, her ex-stepfather shot her mother through the head. Trethewey writes that this short book was “a long and painful journey to write.” The myth of Cassandra helps Trethewey raise the memoir above a clinical account and face her inability as a child to speak out against her terrifying stepfather. The haunting question is why did her mother, an educated social worker, marry a bad man? She eventually divorced him and contacted law enforcement, but too little too late. There’s a jarring contrast between Trethewey’s lyricism and the transcription of threatening phone calls her mother received. The abuser/murderer would accept no logic or “truth” but his own.

The starkest of the books above is Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, by Pulitzer Prize winner and former U.S. Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey. Though familiar with Trethewey’s poetry, I did not know of the trauma that haunted her: when she was nineteen, her ex-stepfather shot her mother through the head. Trethewey writes that this short book was “a long and painful journey to write.” The myth of Cassandra helps Trethewey raise the memoir above a clinical account and face her inability as a child to speak out against her terrifying stepfather. The haunting question is why did her mother, an educated social worker, marry a bad man? She eventually divorced him and contacted law enforcement, but too little too late. There’s a jarring contrast between Trethewey’s lyricism and the transcription of threatening phone calls her mother received. The abuser/murderer would accept no logic or “truth” but his own.

Authors must confront how to depict abuse without flattening the woman to a dire statistic. I face that in my fictional Twin Cities mysteries. Detective Deb Metzger has expertise in domestic violence, but that doesn’t make her a constant “expert” in understanding silenced victims or dealing with imperfect noisy ones. For a teen victim in Should Grace Fail, the transition to survivor appears rough, uncertain, and also comic.

In researching that mystery, I became familiar with a national hotline and resources in my area–The Hope Center and MNCASA.

Back to April, it is the time of pilgrimages. I am not heading to Canterbury like Geoffrey Chaucer’s tale tellers but to the Survivors Memorial in Boom Island Park. Minnesota artist Lori Greene has created colorful mosaic slabs, parts brought into wholeness, to honor and heal women who have suffered and survived. Such beauty is an act of effort, a gift of grace, and, when so much is severely battered, the choice to hope.

Artist Lori Greene