Heroes, Alfred Hitchcock, Pandemics, Cary Grant, and Formulas

That crop duster. The cornfield. Watch it.

Isolated at home during the Covid-19 pandemic and a dreary rainy spell, I watched in Technicolor glory Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 film North by Northwest. Its lumens were intensified by the star power of Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint, and James Mason. Cinematic thrills when my day was a dull formula of chair-bound tasks.

Alfred Hitchcock, Hitch, loved adapting a formula. The screenwriter Ernest Lehman wanted to concoct the ultimate Hitchcock film with North by Northwest, and it felt quintessential as I watched. (Homestay gives me time to think of words like ultimate and quintessential.) That Hitchcockian feel results from the archetype of an everyman, less often an everywoman, rising heroically to the occasion. The plight makes the man.

Hitch’s favored plight is the innocent bystander—“innocent” but increasingly resourceful—embroiled in a deadly espionage intrigue. He is attractive and witty, white and privileged. He becomes involved with a romantic interest on a train to double the danger, is nearly undone in a public space, and is pursued across a threatening landscape. His nemesis is an evil schemer. Nonetheless, our hero figures out how information is being conveyed to an enemy power, stops that transfer, and wins the girl. In saving himself, the hero saves the world order.

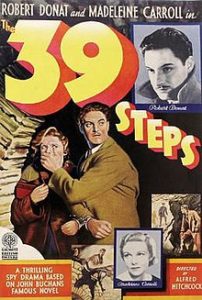

This the pattern of The 39 Steps from 1935 with the character Richard Hannay (Robert Donat with a silly mustache) and Pamela (Madeleine Carroll). The 39 Steps anticipates Hitchcock’s 1938 venture, The Lady Vanishes. The latter focuses on the female lead, a spirited young woman having a travel break before settling into dull marriage. The character Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood, a rare non-blond in the Hitchcock canon) is about to board an Alpine train when a plant pushed off a sill to kill another person hits her instead (the innocent is wrongfully targeted in the formula). The nonfatal blow confuses her. On the train she has tea (pay attention to the tea) with an old woman in tweed, how veddy British. Then the lady vanishes, and nobody but Iris claims to remember her. A brain surgeon on board blames Iris’s “hallucination” on her concussion. In such films, do not trust men like the surgeon who speak with level authority. Iris is eventually believed by a man she initially despised, Gilbert Redman (Michael Redgrave with a silly mustache and about to become very famous). At peril to themselves, the couple has to unwrap the case to find the lady, and along the way convey key intelligence to a homeland on the edge of war.

By the time Cary Grant assumes the role, the silly mustache has gone away. Hitch first considered that everyman’s everyman, Jimmy Stewart. Stewart had starred in the The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), itself a remake of Hitch’s 1934 film of that name. Again, the hero, Stewart, is an innocent caught up in international intrigue, and co-hero Doris Day is allowed to go deeper than her smile (she also sings Que Sera, Sera). The emotional stakes are high with a kidnapped child. The tension is at last relieved with the corny closing line, one of Hitch’s jokes. But the role evolved to suit Cary Grant, who made North by Northwest suave, glamorous. The gray suit he wore has its own following. Yet the Hitchcock leading man does have traits that appear less than heroic.

This is most obvious with Redgrave/Redman, first seen as a collector of folk music playing a recorder for thumping dancers. (Has James Bond ever played a recorder?) Donat/Hannay looks slick. But he’s from Canada. A naïve provincial. Grant, tall, handsome, and graying, dominates any space he enters. As Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest, he first appears on a New York City street as a charming cad moving with purpose, except his ad-man purposes like “think thin” are superficial. He patronizes his secretary and tasks her with writing “sincere” notes to the women in his life. However, Grant/Thornhill is tied to couture apron strings—he has “Mother” (Jessie Royce Landis). It is his attempt to send a telegram to Mother that puts him in the sights of spies, who mistake him for their enemy counterpart, George Kaplan. A mix-up of course, like the public soon mistaking Grant/Thornhill/Kaplan for a murderer.

There has to be a bad guy. Forget Psycho and psychos for the time being (but you can add Foreign Correspondent of 1940 to the espionage mix). For his quasi-political thrillers, Hitch favors the devious sophisticate whose accented tones are so controlled that you know he lacks a telltale human heart. In North by Northwest, James Mason as Vandamm is the brilliant exception that proves the rule—at two points in the film, words fail him. With perfect articulation, Mason/Vandamm uses his mistress, Eva Marie Saint/Eve Kendall, to keep track of Grant/Thornhill/Kaplan. Eva/Eve has the modulated coo of a seductress, as if she’s always about to breathe a sexy ooh. That low voice covers her intent(s), until she has to be “real” in the climax. She lures Grant/Thornhill into a trap that unlike most traps is out in the wide open, under the sunny skies of a Midwest prairie (which was shot in California).

When Grant/Thornhill survives the crop duster scene, he confronts Mason/Vandamm at an art auction and insists in so many words that Eva/Eve threw her entire being into seducing him, a too-willing whore. The villain, who had been caressing his mistress’s slender neck, speechlessly drops his hand. Then the smooth articulation returns: “Has anyone ever told you that you overplay your various roles rather severely, Mr. Kaplan?” This may be an inside-Hollywood joke, but Grant/Thornhill next saves himself by overplaying the role of auction bidder. Mason/Vandamm loses his cool again when his “right arm” Leonard (hawkishly handsome Martin Landau) reveals a betrayal. Urbanity returns in the denouement when Mason/Vandamm delivers a meta-line on the suspension of disbelief. He remarks to his captors that it seems “unsporting” to use real bullets, and of course no real bullets were used—it’s a film, a fiction. Hitch flavors his suspense with tongue-in-cheek remarks and irony. The free world is saved by people clambering over the heads of presidents at Mt. Rushmore.

North by Northwest has more to recommend it. The formidable geometry and geography—the UN building, the treacherous coastal highway, the crossroads, the cantilevered house, the mountain. Eva Marie Saint’s wardrobe from Bergdorf Goodman. Leo G. Carroll, The spiky music by Bernard Herrmann. It’s a grand illusion, an escape with the red-carpet treatment of The Twentieth Century Limited Train.

In this time of crisis, the scientific formulas, the economic formulas, and the formulas for being a responsible community of helpful individuals are undergoing constant change. It’s been unusual to do one’s duty by amusing oneself at home. As authorities plot what could or should happen next, with competing scripts revised daily, it is heartening to think that an everyman and an everywoman, without having planned or trained for a pandemic, can become a hero.

So love this! My wife and I have been working through the Hitchcock filmography movie by movie and we’re still in the 1940s. But I’ve seen all those 50s and early 60s films already, of course, and do so love North by Northwest. Great revisit here!